Conquering Mountains: My Journey Of Healing Along Nepal's Annapurna Circuit

In the fall of 2016, following the darkest season of my life, I stepped foot on the Annapurna Circuit in Nepal to begin an almost two-week trek through the Himalayas… entirely alone. Without a map, training, experience, or a guide, I was unprepared both physically and mentally for what was to come.

The Mountain

Waking up with the sun, I scooted my aching legs to the side of the tiny wooden bed, examining my wounds.

My right ankle had swelled up to the size of a softball overnight, from some misstep on loose rocks the day before.

I yelped as my foot landed with a thud on the dusty wood-planked floor, searing pain shooting through my entire leg. But of course, as usual, no one was around to hear me. No one in Upper Pisang, a little village tucked away somewhere in the Nepali Himalayas, anyway.

Minutes passed as I caught my breath, fighting back tears, and glaring at my mud-caked hiking boots perched in the corner of the room, with the hatred of one thousand suns.

Rule number one of hiking the Annapurna Circuit: break in your hiking boots before the trek.

Rule number two? Bring a map.

It’d been a steep learning curve.

Bastien, one of the few fellow trekkers I met along the way, admires a temple hidden in the woods. Many of the photos you see of me in this post were taken by Bastien during the hours that our paths crossed!

I reached over to the socks hanging on the window sill next to the bed. The sweat had dried from the previous day, but they were still stained in blood. It wasn’t clear whether that was from the quarter-sized blisters wrapping over the soles and tops of my feet, or from the dozens of leeches that had decided all at once to prey on my foot a few days back. Probably a bit of both.

Blood and sweat aside, these were the only socks I had with me for my two week journey through one of the toughest trails in the Nepali Himalayas, across 140 kilometers (87 miles) of terrain and ascending 5,416 meters (nearly 18,000 feet) into the clouds: the Annapurna Circuit.

The Leeches

Actually, these socks belonged to a young man named Carlos — one of the few I’d encounter along the way, and who was kind enough to lend me a pair of his socks when we realized mine didn’t fit properly and were contributing to my monstrous blisters.

Rule number three: bring the right socks.

View from a teahouse on the first morning of the trek. Waking up to these rice paddies and lush green mountains was unforgettable!

Carlos and I had only crossed paths briefly, with enough time to openly spilling our soul to one another, and our blood. We’d both been surprised to arrive at the teahouse door and find our ankles and legs covered in leeches, impulsively jumping around like crazed monkeys as we tried to scrape the blood-sucking worms from our skin.

Leeches are strange little creatures. They don’t carry disease and can’t do much actual damage, but they do inject in their prey a numbing agent and an anticoagulant to stop the blood from clotting and to keep the victim unaware. When 20+ of them all prey on a person’s feet at once, it’s a mess.

Carlos and I made the best of it, chatting on the teahouse patio well into the evening, our host occasionally splashing the wooden floor with buckets of water to wash off the pools of blood that had collected beneath us.

Apologies for the graphic image, but I couldn’t NOT share this photo of the bloody aftermath of my first (but not last) leech-attack of the trip. As strange as it sounds, this ended up being one of my favorite memories from the trek!

Typically, leech bites will bleed for 10 or more hours, so Carlos and I had plenty of time to talk. I shared about the year from hell that brought me to the Annapurna Circuit, and he shared his story as well. He lent me some socks because, as he pointed out, the ones I brought were not intended for treks. Hence that massive blisters.

The next morning, we started off together after a 5am breakfast, but it wasn’t long before it became obvious that I was slowing him down.

“I’m fine!” I lied. “I promise!” I hoped, smile plastered on my face. Carlos nervously wished me well before disappearing into the trees ahead. The only thing worse than feeling held back by my own body, was dragging another person down with me. I wondered if I’d see him on the mountain again.

Probably not. It wasn’t unusual to go days without seeing another hiker on this trail. It was monsoon season, after all — notorious for spontaneous downpours, landslides, and, of course, leeches.

Monkeys perched at Pashupatinath Temple in Kathmandu, Nepal

The First Steps

Back in my teahouse in Upper Pisang, I stretched the filthy socks over my swollen, bandaged feet. I couldn’t believe the stains of blood were just from a few days before, back when leeches seemed like the toughest hurdle to overcome. It felt like an eternity had passed since them.

I reached for the hiking boots. No matter how tenderly I tried to squeeze my feet into those boots, exercising the precision of a heart surgeon to avoid twisting or touching my ankle any more than necessary, the pain was excruciating.

With the aid of my hiking poles, I pulled myself up and took my first step of the morning, the pain knocking the wind out of me. Hesitantly, I hoisted my backpack — a medium-sized, cheap knock-off Deuters one I’d picked up in Kathmandu — onto my back and fastened the waistband around my bruised hips.

One more step— wince; then one more, then another, until I was outside my little teahouse room and could see the trail beginning ahead.

Prayer flags strung overhead in a village along the Annapurna Circuit

In order to reach the next major village, I’d need to walk approximately 20 km today, abruptly climbing a 400-meter mountain before descending again on the other side. I heard the view at the top was beautiful but I wasn’t sure I really cared.

Tears streamed silently down my cheeks, leaving streaks of dirt on my skin. I hated this. I wanted to quit. I wanted someone to give me permission to quit, or to tell me it would be okay or to offer some kind of solution or to just give me a hug.

But there was no one. I was completely alone, staring up at the daunting trail ahead, under the weight of my over-stuffed Deuters backpack and overwhelming regret that I’d brought myself here in the first place.

The Test

I have absolutely no idea what possessed me to hike the Annapurna Circuit.

To be clear, I had always been an adventurer, but not so much a hiker or a trekker. And at that time, not so much at peak physical fitness, either. So, yeah, this was definitely a strange choice for me.

Not only was I physically unprepared, but I’d also be venturing into the Himalayas during monsoon season, which meant leeches, landslides, and solitude (the silver lining being that I would have the mountains to myself, because apparently no one wants to hike Annapurna in landslide-and-leech-season . . . go figure).

In fact, I’d only started exercising about a month before this trip, when the stress of studying for the Washington, D.C. Bar Exam became unmanageable and my desire for an escape became desperate. I obsess over physical fitness nowadays, but at that time in my life, only desperation could have brought me into a gym, and that came in the form of the Bar Exam.

Rooftop view from my hostel in Kathmandu, Nepal

In America, after completing three brutal years of law school, students are then rewarded with three more miserable, sleepless months studying ridiculous scenarios within every legal topic under the sun — things like how the federal tax code applies to addicted gamblers, and what property rights exist for estranged spouses who’ve become squatters who’ve become addicted gamblers.

The two- or three-day Bar Licensing Exam concludes in the same way, always, for everyone who takes it: you walk outside, dazed, sleep-deprived, processing the grief of certain failure, realizing all those years of hard work and student loan debt were worthless because you won’t even have earned a license to practice law.

Anyone who walks out of the Bar Exam boasting of confidence most likely either a) cries himself to sleep that night or b) will be retaking the exam next semester. I mean it.

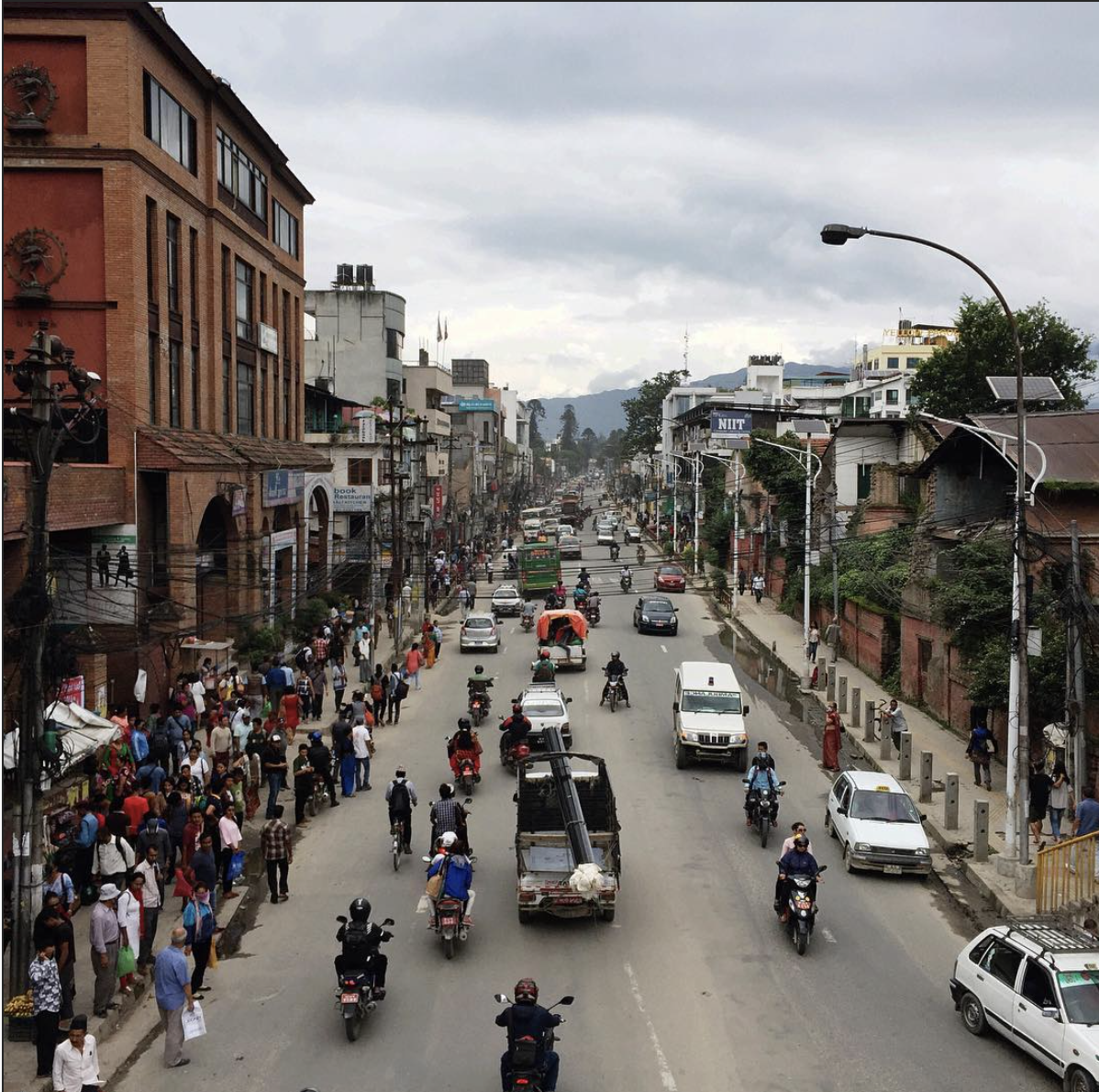

Traffic in Nepal’s capital, Kathmandu, where I spent a few days before the trek shopping for gear and preparing.

The grief process culminates in what’s known as a “Bar Trip,” where law students all over America run away from their problems to some far away corner of the world to remember what it’s like to be happy again.

I decided to volunteer. International service work was something I’d always loved; it’s what stirred in me a desire to attend law school in the first place, and it was something I’d neglected since enrolling.

It was also the best way, I figured, to get my mind off my own problems.

For me, the possibility of failing the Bar Exam was the least of my concerns. The last few years had been a living hell of their own.

The Break

I signed my divorce papers at a laminate wood desk in the George Washington Law Review offices, located in a basement on 20th Street and G Northwest in Foggy Bottom, Washington DC.

I’d been elected as an editor of the Law Review — a prestigious, student-run legal publication — for my final year of law school. And after being pushed out of my church and losing nearly every DC friend I once had under condemnation for leaving my marriage, this office became my home, and the editorial team became my family.

It also was the only place where I had access to a free scanner and printer in Washington, D.C., so it was in these offices where I finally put pen to paper and made the thing official.

The divorce was a long time coming. I got married on a beautiful spring day at the age of 21, to a man who wooed me with a lot of false promises and a precarious ultimatum. Our lives looked perfect from the outside — a fairytale wedding; a charming blue rowhouse on Capitol Hill; he, an entrepreneur and me, a promising young law student; fancy vacations and Instagram-worthy dinners and volunteering in the church band.

But behind closed doors, life was hell. Shortly after we exchanged vows on that perfect spring day, something shifted in this man I’d promised to love forever. His strong convictions and great leadership abilities and charisma revealed their darker sides, twisting into manipulation, control, deceit, and cruelty. The emotional abuse picked away at my self-confidence, my voice, my sense of worth, and my will to live.

For those first two years as a young married couple in Washington, D.C., I struggled with severe depression and suicidal thoughts. Despite confiding in friends, I was met either with disbelief or judgment. I felt stuck, hopeless.

Then, the summer after my second year of law school, as I contemplated drastic measures to escape my reality, my best friend Brittany gave me advice that saved my life: she told me to pack a bag and get out.

I know it might seem an obvious solution to you, but leaving never seemed feasible to me. I’d been suffering under the delusions of my depression, combined with the fear of rejection, scorn, and fallout that would ensue, and otherwise reasonable solutions appeared impossible to me.

Brittany was the first person in my life to ever suggest that was an option and, even, a better option than the alternatives I was considering. She reminded me that although I couldn’t control my dysfunctional relationship or the people around me, I could control my own two feet — I could choose to save my own life.

I went home that evening and told my then-husband that I’d had enough. Shaking under his fiery protests as I shoved some clothes into a duffel bag and made a call to the one friend I knew wouldn’t turn me away when I showed up at her front door.

A larger teahouse in Manang, which is one of the biggest villages along the Annapurna Circuit and a popular spot for trekkers to take an “acclimatization” day before attempting the two- to three-day summit. I hiked a nearby mountain on my acclimatization day because I worried that a full day of rest would hurt my momentum, and then returned to Manang to sleep; the key is to sleep at the same altitude two nights in a row.

The separation and divorce process dragged on for one very long year, as more-or-less required under DC law. During that time, I was rejected and abandoned and condemned by the people in my community who’d once felt like family. My depression worsened, and I coped with a bottle of wine each night and, on occasion, bouts of self-harm.

Truthfully, it’s only by the grace of a loving God and a whole lot of therapy that I persevered through that final year of law school, even being elected as a Law Review Editor, graduating with honors, and managing to make new friends.

Then, just a few days before accepting my diploma on that stage in the George Washington University auditorium, I signed the papers on that laminate wood desk that made everything official: I was finally, legally free from my toxic relationship. My law school diploma bore the name I hadn’t used for three years: Alexandra Saper.

View from the mountain outside Upper Pisang — the hike was one of the most difficult of the trek, but view from the top was remarkable

Months of tedious Bar Exam study ensued, and God slowly pieced together my life and faith in the meantime. Healing came from just knowing this horrible chapter of my life was over, albeit not without some scars — both figurative and literal — that would endure for years.

The end of summer crept closer, and while my law school peers made plans to drink wine in Italy or go on a cruise around Croatia or party in Cancun, I needed a real distraction. So I planned an around-the-world service trip, starting with volunteering at an orphanage in Zambia, a quick stopover in Abu Dhabi, and finishing with a month working at an anti-trafficking ministry in Bangkok.

There were two unaccounted-for weeks in between the two service projects, so I looked at a map and spotted Nepal, a tiny land-locked country situated somewhere between Zambia and Thailand. I’d never been to Nepal. I didn’t know anything about Nepal, except what I remembered from an old high school friend who had visited years before. She’d said the hikes were nice.

I ran a couple of Google searches and within a day, about two weeks before I’d leave the United States, I decided I’d hike the Annapurna Circuit, all alone, without a guide or a porter or any freaking clue what I was getting myself into.

The Purge

The night before I began my trek, I sat on my cozy bed in my cozy hostel after taking what would be my last cozy shower of the journey, staring blankly at the 16-liter knock-off Deuters backpack I’d picked up in a shop in Kathmandu earlier that afternoon. The same backpack that I planned to carry across 140km of mountain terrain and ascending 5,416 meters toward summit at Thorong-La Pass.

I’d just tossed the tiny travel-sized bottle of shampoo in the trash in an effort to pare down the items I’d optimistically shoved in my backpack – soap: out; three extra clean shirts: out; tweezers: out; razor: out; dignity: out.

I’d wear the same shirt and the same pair of socks for the next ten days. I wouldn’t shower and I wouldn’t shave my armpits but I also probably wouldn’t run into many other humans along the trail, anyway.

All that remained were the basics: gloves; hiking poles; a waterproof jacket to help with the inevitable monsoons; snow pants; one pair of leggings; a shirt and shorts to sleep in; two short-sleeved shirt and one long-sleeved shirt; a fleece jacket for when I reached the snow-covered summit; a few energy bars; a small plastic bag with a few Tylenol; deodorant; a self-purifying water bottle; and some sparkling new hiking boots I’d picked up from REI right before leaving America.

Curse those hiking boots.

The pack was still heavy, but manageable, and I hoped I’d just get used to it after a couple of days.

I hoped for a lot of things that night before I started my trek. I hoped I’d know what to do when I stepped off the public bus at the start of the trail. I hoped I wouldn’t get injured, especially because my first aid kit didn’t make the cut when I purged my overweight backpack. I hoped I wouldn’t encounter leeches (I did) and I hoped I wouldn’t go mad from loneliness (I didn’t).

I hoped I wouldn’t get lost and I hoped I’d find what I was looking for . . . some peace or closure or dramatic awakening from the nearly fatal season of life from which I’d just emerged.

I hoped one more time for no leeches.

I picked up this trekking “map” a couple of days into my journey. It marks the villages along the route, charting the respective altitudes, distances between stops, and estimated hiking time. My plan was to spend ten days hiking the 140km between Besisahar and Jomson, at which point I’d hitch a ride to the lakeside town of Pokhara for a few days of rest and recovery.

The Climb

The first few days of hiking came as a shock, as any reasonable person (myself excluded from this category) would have expected. On day one, I hitchhiked around a landslide in a vehicle that hit a cow and almost slid off a cliff, before it stopped and let me out. The cow was fine.

Deciding I’d better stick to my own two feet, I carried my Deuters backpack over slippery wet suspension bridges, and through rice paddies, tiny Nepalese villages, and – yes, we knew they were coming – leeches.

For the most part, I suffered my days of hiking in private, because the trails were, as predicted, basically deserted. Most days, I’d walk around 15-20 kilometers, climbing hundreds and then thousands of meters in altitude and feeling the weight of the thinning air with every new level of the ascent.

Some days, I moved much slower.

One of the many suspension bridges and the only way to cross over the rivers along the Annapurna Circuit.

Only a few days in, I could count ten blisters on each of my feet, some the width of a golf ball. The blisters formed almost instantly when I began my trek, and became so inflamed and painful that I could hardly walk by the end of my third day of hiking.

Just when I couldn’t walk any further, I finally came across a small village called Danaqyu. Checking into the first teahouse I found, I met two Israeli soldiers — the only others who seemed to be staying in the village and some of the only two people whom I’d meet on the entire trek.

They saw me limping and looked at the abysmal state of my feet, telling me that the pain would only get worse if I didn’t do something to relieve the pressure.

So that night, with some tiny scissors they’d found in their first aid kit, I laid on the teahouse’s kitchen table as one soldier pinned down my shoulders and the other began cutting into the bottoms of my feet to remove the skin covering the massive blisters. I bit down hard onto a towel to muffle my screams, and they doused my wounds with some alcohol found in the kitchen, before wrapping my feet in bandages they retrieved from their packs.

Sitting at a monastery in Manang, picking thorns out of the hiking socks Carlos had lent to me.

After a restless night, I awoke early to begin the next day of hiking. In addition to my bandaged feet, I was marked by bloody welts around my waist and shoulders from the straps of my backpack, and blistered hands from overcompensation for my foot pain by supporting myself too heavily on my hiking poles.

Without a map, I took too many wrong turns in an attempt to seek out “shortcuts,” finding myself scrambling up the sides of crumbly mountains. My feet did feel a bit better from last night’s makeshift foot surgery, but the pain still made me unsteady — causing me to slip on some loose rocks on a “shortcut” and sprain my ankle.

I was, truly, in a pathetic state by the time I finally reached Upper Pisang that evening. I’d made it this far, but just barely. I limped inside, devoured a bowl of dal bhat and rice, and slept hard.

It was the next morning, with bandaged feet, a bruised body, blistered hands, and a sprained and swollen ankle, that I stared up at the Upper Pisang trailhead snaking its way up the mountain before me, wondering how the hell I was going to continue onward.

Prayer wheels like can be found all along the Annapurna Circuit trail. Spinning them as you walk by is supposed to bring good luck, according to local beliefs.

The Way Out

The thing about being all alone on a mountain somewhere in Nepal is that your options are rather limited. I was in pain, bloodied and bruised and blistered, but I had no medical equipment or nearby hospitals or Israeli soldiers to help fix it. I was exhausted, but what would quitting even accomplish? It would only leave me stranded in some strange village without cell service until the end of time.

I really just had three options that morning in Upper Pisang, the same options I’d have every morning on the Annapurna Circuit: 1) keep walking up the mountain; 2) turn around and walk down the mountain; or 3) stay still and prolong the inevitable, which was either walking up or walking down the mountain. All options ultimately required walking.

I might as well walk upward.

So that morning in Upper Pisang I made the decision to take a step. Just one. I blinked away more tears. Then another. God, this hurt. Then one more.

The trailhead inched closer.

One more step. Another. One more. I moved further and further one painstaking step at a time.

Each day on that trail would start the same. I’d squeeze my feet into those brand new hiking boots, scream and curse and cry at the nothingness around me, and then take my first step through blinding pain. I’d panic, trying to think of any way out of this.

Nope, no ideas. No way out.

I’d take the next step. More blinding pain, more screaming and cursing.

And then the next step, and the next, and the next. I’d keep taking step after step until my pain had moved somewhere outside of my body – not that it went away, but that I could recognize it was there just like I would recognize the birds around me or the cooling air as I ascended the mountain. Within the first hundred steps, I’d accept the pain and adjust to my new normal, and could continue onward.

Drinking tea and soaking in the view after hiking the 420-meter mountain outside of Upper Pisang.

That day in Upper Pisang I took one step after another, until I’d walked 20 kilometers worth of steps over a 420-meter mountain to reach a village called Manang.

I felt, well, stunned at what I’d accomplished . . . at what my body and mind could do despite pain that seemed nearly insurmountable.

The pain persisted, but so did I. It didn’t control me anymore.

That night in Manang, I hung my sweaty clothes to dry and rested my aching feet on my wooden bed, replacing the bloodied bandages with the last clean ones that the Israeli soldiers had given me.

I slept harder than I ever have in my life.

And then, the next day, I woke up and did it all over again.

View from the mountain outside Upper Pisang

The Beauty

As physically strenuous as the trek was, it was countered by the immeasurable beauty of the Himalayas — scenes that would shift from sweltering tropical jungles, to mountain valleys laced with streams, to chilly pine forests surrounded by snowy peaks, to desolate desert, and eventually to terrain looking something like the surface of the moon.

Of course, as the altitude increased, the climate and the environment changed accordingly, highlighting the impressive distances I’d managed to travel by mere foot.

A local Sherpa woman rests alongside the trail as she travels between villages. The Annapurna Circuit is also a common route for local traders.

I’d pass though 100-foot cascading waterfalls, tiny villages filled with tiny wood (or, at higher altitudes, stone) homes, fields of wildflowers in every color imaginable, rushing rivers, and herds of wild goats and horses and yaks.

Even in sections of the densest forests, I’d find colorful Hindu prayer flags strung through ancient temples and golden prayer wheels, like ribbons decorating a present — quiet, comforting reminders that others had been making this same journey for centuries before me.

Gently spinning the prayer wheels as I passed through felt like an initiation into some secret, ancient club — an initiation that, I suspected, would bind trekkers long after they stepped off the Annapurna Circuit.

At higher altitudes, trees became sparse, so wood houses were replaced with little stone huts.

And while the untouched nature couldn’t have been more beautiful, it was the Nepali people I met on the journey that softened my spirit and brought rest at the end of each weary day. In all my years of traveling, I still think that Nepali people are some of the kindest on the face of the planet. And although I’d rarely see other trekkers on the mountains (save for Carlos from Guatemala, Bastien from France, and the two Israeli soldiers), every evening, as I’d pass through a village searching for a meal and a place to sleep, I’d have the luxury of meeting the local Sherpas.

Smiling hosts welcomed me into their homes for endless heaps of rice and warm bowls of dhal baht and momo (Nepali dumplings stuffed with meat, vegetables, or wild mushrooms in some parts of the mountains), and as much curious conversation as I could sustain every evening. Each morning, as the sun was rising, I’d sit for a home-cooked breakfast of chapati (a kind of fried flatbread often served with eggs in the morning) and muesli, before being thanked and blessed by my hosts and sent on my way.

The landscapes of the Annapurna Circuit, especially during monsoon season, were extraordinary. But the people were no less of a masterpiece.

Goats pass through a village in a jungle-covered area at the beginning of the trek. Jungles would become pine forests and then desert as the trek continued and altitude increased.

The Summit

Both literally and figuratively, my journey along the Annapurna Circuit brought me through the highest peaks and some of the lowest valleys. Summit was no exception.

Thorong-La Pass is the highest navigable pass in the world, and is the highest point on the Annapurna Circuit. At an altitude of 5,416 meters (nearly 18,000 feet), there is no vegetation, no shelter, and no possibility of lingering for long without an external oxygen supply.

To properly acclimatize, trekkers generally spend five nights between their arrival in Manang, the last major town before summit, to crossing Thorong-La over to Muktinath, the typical post-summit stop located at the foot of the Pass.

It was during this stretch of the trek that I watched my typical ten-hour hiking days decrease to about three hours, and my daily ascensions drop from upwards of 1000 meters per day to a mere 200. Hiking 10 steps at 5,000+ meters feels like trying to run a marathon with a towel wrapped around your face.

Sunrise at Thorong-La Pass, the highest navigable pass in the world.

Regardless of how physically exhausting the hikes became, there was also concern about acute mountain sickness (also known as “AMS”), which could befall even the most experienced trekker at those heights. Symptoms of AMS include vomiting, headaches, sleeplessness, dizziness. If not addressed, hikers risk developing a buildup of fluid in the lungs and brain, as their AMS transitions into fatal High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (“HAPE”) or High Altitude Cerebral Edema (“HACE”).

Rumors spread throughout the villages on the Circuit of a trekker just a two weeks earlier who went to sleep with pounding headaches and never woke up the next day. Warning signs were posted in every village.

Ascending slowly may have been necessary considering how strenuous the climb was, but it was also a strategy.

On the day before summit, I hiked only two hours. I spent those two hours swallowed up by a thick cloud, as I navigated a steep and desolate mountainside and gasped for air every few seconds. It was two hours of a new kind of meditative rhythm: one involving taking three comically slow steps, followed by a minute of rest to catch my breath; then three more slow steps, and so on, until I reached High Camp where I’d sleep for the night.

Above the clouds on the most barren, moon-life mountain top outside of High Camp. The earth was littered with shards of rock making the scene feel especially eerie.

These were two hours of the most difficult, exhausting, and visually haunting hiking terrain I’d experienced up until that point. High Camp sat at 4,850 meters.

I’d like to say I slept like a rock that night at High Camp, exhausted from the day’s hike. But the reality is that my AMS symptoms were more severe than I admitted at the time.

Between unnerving hallucinations, splitting headaches, nausea, and sleeplessness, any medical professional or fellow trekker (and all the warning signs posted along the trekking route) would have advised me to urgently descend and take time to acclimatize. Immediately descending to a lower altitude is, point-blank, the only advisable treatment for AMS.

But by the time I came to terms with my altitude sickness, the sky was dark, and descending seemed risky as well. I blamed my hallucinations and headaches on dehydration, and attributed my fever and cough to a cold I’d had a few days back.

No plants or animals live at the altitude of High Camp, but horses are used to transport locals up and down the summit for trading

I regret the decision I made to not descend that night, and can’t stress enough the importance of listening to your body when it begins to show signs of AMS or HAPE. There is no courage or strength or wisdom in “pushing through” — I promise you, it’s just foolishness.

This is something I know now, but at the time, I tried to ignore and downplay my symptoms. In some metaphorical way, turning back and descending felt like weakness, and it felt like failing. I’d just caught up with Carlos, and I wanted to return his socks to him at the end.

So I shut the door of my tiny stone hut at High Camp, layered on every article of clothing I had in my backpack, crawled into my sleeping bag, and prayed that I’d just wake up the next day.

Sunrise at Thorong-La Pass, the highest navigable pass in the world.

I tossed and turned for hours, managing an hour or two of sleep that night. My alarm sounded. 3:30 AM. It was the morning of summit and I survived the night.

Stuffing my sleeping bag in my backpack and lacing up my boots, I didn’t bother shedding any of the layers of clothing in which I’d slept. I’d never been so cold in my life.

In the pitch black that morning, I hiked along the narrow ledge of the mountain led only by the light of my head torch and the crescent moon overhead. I was shivering and trying to talk myself through a piercing headache and increasing nausea. It was important to reach summit before the harsh daytime winds made Thorong-La Pass unpassable.

That, and I wanted to watch the sunrise at 5,500 meters.

A trekker climbs toward High Camp on the desolate mountainside, somewhere around 4,800 meters altitude

Three hours later, there it was. A sunrise above the clouds at the highest navigable pass in the world.

Standing above the clouds, with orange and fuchsia skies reflecting off snowcapped peaks, I soaked in a view of the world higher than almost any other human on the planet that morning.

But as beautiful as that sunrise was, I couldn’t appreciate it much longer than 10 minutes. My fingers and toes were numb from the cold and I was losing control of my shivering body. Plus, it’s not advisable to stop at Thorong-La Pass for more than a few minutes without external oxygen. My headaches had worsened.

Sunrise at Thorong-La Pass, the highest navigable pass in the world.

Victory at summit! I could only stand maybe 10 minutes at Thorong-La Pass before the freezing temperatures, hunger, and altitude sickness forced me to descend.

I was finally ready to descend, and I did so quickly, stumbling down the other side of the mountain to find warmth and food. Hours passed before I finally arrived at the first town on the other side of summit: Muktinath. The headaches persisted, but I was starving. After devouring a plate of food, I attempted to descend further. But it was long before I fell to my knees, vomiting into the dirt and eventually curling up in a ball on the side of the road, unmoving.

In my barely lucid state, what happened that day is bit of a blur. I do remember Fiona, a young English woman who emerged from thin air, organizing a team of reluctant Nepali men to lift me into their truck and drive me down the mountain to recover at a lower altitude.

I remember the truck pulling over periodically to let me vomit, before continuing down the mountain.

This, of all the days on the Annapurna Circuit, was a day of the most spectacular highs and the most terrifying lows. Reaching summit by sunrise was one of those highs, as was the angel named Fiona who made it her mission to rescue the 5’ 1” American trekker she found shaking and unconscious on the dirt.

Morning views at Thorong-La Pass, the highest navigable pass in the world.

The Mantra

In the days leading up to Nepal, I’d anticipated emotional and mental healing to come through hours of thinking, processing, working through things with analytical ferver. I could envision replaying the things that had happened to me those past few years, and the things I’d done, crying on mountainsides and wrestling with those internal demons in some dramatic, symbolic, Hollywood-style montage.

But in reality, on those mountains, I didn’t think much about anything. It might come as a surprise to you that being completely alone for so many hours over the span of 10 days wouldn’t produce some kind of Odyssey-length internal dialogue, but the truth is that my thoughts were consumed with walking.

The eerie landscape at High Camp, the afternoon before summit

The first couple of hours of each morning required so much effort to just take my first steps and to keep moving. So, this “take one step; now breathe; one more step; breathe” mantra lured me into some meditative state that would persist throughout the day until I collapsed into bed at around 8:00pm each night.

So, I learned to breathe. I learned to take the next step through blinding pain when it was the last thing I wanted to do. When everything inside of me said it was impossible.

Because, well, what other option did I have?

And I learned that these steps would ultimately take me to my destination, supported by the strength of my weary, injured, seemingly useless feet. I was a whole lot stronger than I’d let myself believe, for far too long.

Day after day on the Annapurna Circuit, I’d slowly rebuild trust in the power of my footsteps to move me forward.

Boats in the lake in Pokhara, a final resting point for trekkers who have completed their journeys.

Even without a map, without training, without a partner by my side, I learned that I could overcome some of the toughest terrain, while still remaining a child in awe of the beautiful world around me and the Creator responsible for it all.

I learned that it was my own two feet, as weak and imperfect and damaged as they were, sustained by dal bhat and the grace of God, that allowed me to overcome everything that Annapurna Circuit threw at me. Even landslides, flash floods, injuries, and leeches.

And it would be these same two feet that would allow me to overcome whatever life had for me when I stepped off that mountain.

The Victory

I’d recommend a map if you hike the Annapurna Circuit. I’d also recommend that you do hike the Annapurna Circuit.

Bring a friend, or don’t. Bring a reliable first aid kit. Wear in your hiking boots before you go like your life depends on it. Ditch the shampoo and the changes of clothing and the pillow and the razor. Give yourself a minute to laugh at the fact that you actually thought you’d shave your legs and wash your hair along the way. You’re a badass, you can handle it.

Heck – I’d even recommend you hike Annapurna Circuit during monsoon season (avoiding the months of highest rainfall . . . I recommend late August), when you can have some of the most stunning pieces of the planet all to yourself, without anyone around to notice your unshaved legs or smell your sweat.

Listen to your body at any signs of AMS. Descending is not a sign of weakness or failure. Knowing when to pause and step back despite the allure of what’s in front of you is a decision to know and love yourself. It’s a decision to practice wisdom and restraint, rather than letting stubbornness and pride control and destroy you.

Three of the few people I met on the Annapurna Circuit. After one of the steepest ascents on the trail, we all rested on some nearby benches for an hour or so, sipping mint tea and soaking in the views.

After resting, the other trekkers and I set out again. Shortly after this photo was taken, we drifted apart, and I was alone again.

Make friends with your Nepali teahouse hosts and with any trekkers you encounter along the way. Make friends with the leeches because there’s really nothing you can do about them. Make friends with the pain and discomfort because it’s all coming along for the journey, too. The experience is truly and unequivocally worth every bit of it.

You may think you can’t do it but you can. If I can do it, you can. You’re stronger than you think you are. And it’s about time you prove that to yourself.

Plus, you’ll have the beauty of the untouched Himalayas to beckon you forward, whispering for you to step, breathe, step, breathe — like a drumbeat to a chorus of chirping birds and gurgling rivers and colorful prayer flags flapping in the wind.

And hopefully, like me, you’ll step off that mountain with more than just stories and photos. After a long shower, after your cuts and bruises heal, after you burn those blood-stained socks, I hope you’ll see something new when you look in the mirror — your very own walking embodiment of a mountain overcome, of a victory.

*If you’re struggling with depression, suicidal thoughts, or an abusive relationship, I want you to know that there is HOPE and you aren’t alone, despite how much it may feel like that. God is angry with how you, His child, has been hurt, and He weeps with you.

But this is not the end of your story, it’s only a chapter in your story. Please reach out to a friend or family member who is safe and supportive, meet with a therapist (I can’t emphasize this enough — I love therapy!), or call a support hotline if you don’t know where to start.

In the United States, the Suicide Prevention Hotline is available 24/7 at 1-800-273-8255. If you live somewhere else, just plug it into Google to find your local support contact.